For the Linux version of Superluminal (a CPU profiler) we make heavy use of eBPF to capture performance data. This is the story about how an innocent profiling session led to a change to the Linux kernel that makes eBPF map-in-map updates much faster.

What is eBPF

eBPF (originally “extended Berkeley Packet Filter”, though now used as a standalone term) is a powerful system in the Linux kernel that allows you to safely run custom programs directly inside the kernel. These programs can be attached to various hooks in the kernel called tracepoints, kprobes, or perf events. You can think of an eBPF program as C code that executes whenever a specific kernel event occurs. An example of this is the sched_switch tracepoint, which triggers on every thread context switch.

Superluminal uses eBPF to collect performance data such as context switches and sampling events.

eBPF maps

Data exchange between a kernelspace eBPF program and the userspace controlling program (in our case, Superluminal) goes through eBPF “maps”. An eBPF map is a shared memory structure that acts as a bridge between kernel and userspace. Each map represents an underlying data structure; examples of map types are arrays, hash maps, ring buffers, and many more.

eBPF programs running in kernelspace can update maps to send data back to userspace. For example, Superluminal’s eBPF backend uses the ring buffer map type to output performance events (such as context switches and samples) from the eBPF program to userspace. The controlling program can also update maps from userspace to make data available for use in the kernelspace eBPF program.

As explained in a previous article, Superluminal makes use of .eh_frame data in a binary to retrieve stack backtraces when sampling. Since sampling happens in kernelspace through an eBPF program as described above, we need to upload the .eh_frame data to the eBPF program from userspace for each relevant binary so that the eBPF program can make use of the data.

The .eh_frame data is stored in an eBPF map of type BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY_OF_MAPS, which essentially represents a 2D-array. In C++, you could express this as a std::vector<std::vector<UnwindRow>>, where there is one entry in the outer vector per unique binary loaded in the profiled process(es) and the inner vector holds the actual unwind data for that binary.

The process to go from a binary to unwind data being available for use in eBPF is as follows:

- The unwind data is extracted from the

.eh_framesection. This is described in the linked article, and is already very efficient. - The unwind data is converted to our internal format that’s highly optimized for speed & memory efficiency.

- The converted unwind data is uploaded to eBPF through the

bpf_map_update_elemuserspace function, which inserts the unwind data for each unique binary into the outer array.

From there on, the eBPF programs can make use of the unwind data.

Performance problems are never where you think they are

It is important that the unwind data is made available to eBPF as soon as possible, since the eBPF code won’t be able to unwind callstacks before the unwind data has been uploaded. To lower this latency as far as possible, we use various mechanisms, one of which is precaching the unwind data before profiling starts. This is done by enumerating the needed binaries (i.e. the main executable, and shared libraries it depends on) for each relevant process and then extracting, converting and uploading the unwind data for each binary to eBPF.

We saw in the previous article that the extract step took much longer than expected, which caused this precaching step to take much longer than we wanted. After optimizing that part, the precache step was much faster, but still much slower than we’d expected it to be.

Fortunately, we happen to be developing a CPU profiler, and what’s the point of that if you’re not going to use it? So let’s profile the profiler to see what’s going on.

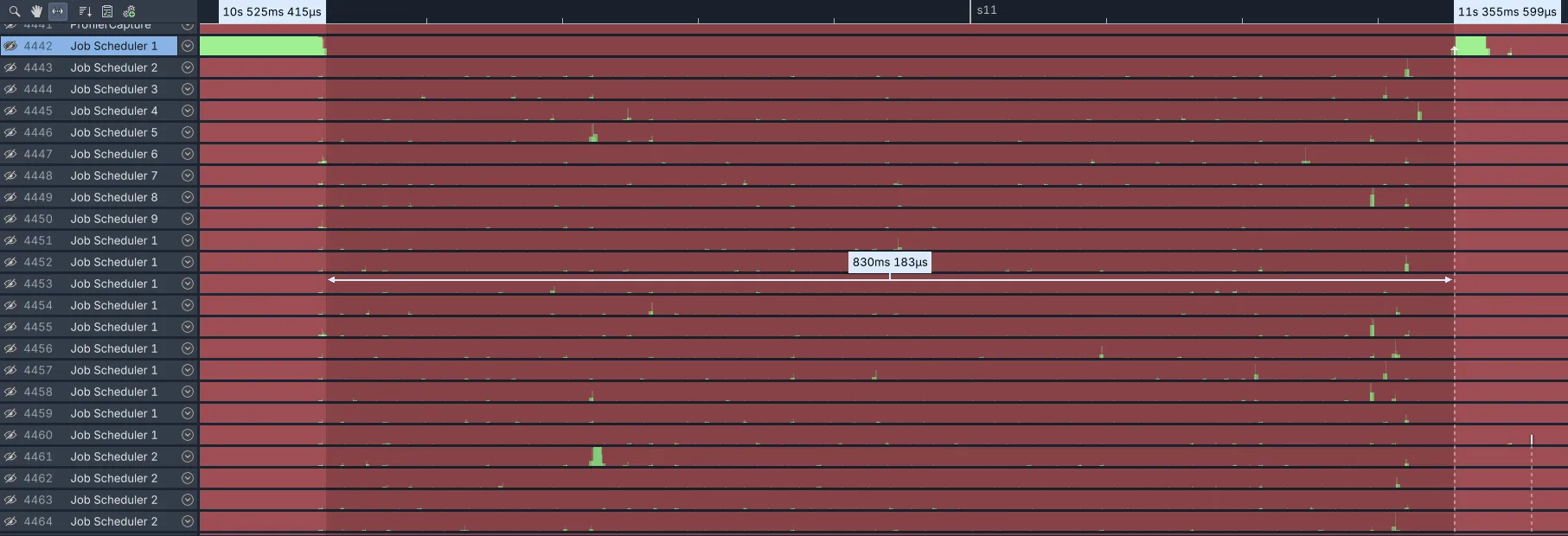

A profile of this part of the capturing process looks like this:

If you’re not familiar with Superluminal, this is showing the wall-clock timeline for each thread in the process. A green color means the thread is executing code at that point, any other color means it’s waiting on something (i.e. a lock, IO, network, etc).

In this test, there are about 1400 binaries that need to be precached, and the profile shows that this step takes ~830ms end-to-end. The actual work of precaching is spread over the available CPUs using our job scheduler: a job is started for each binary, where each job does the extract/convert/upload for that binary, and then inserts the uploaded data into the outer map.

I’m testing on a machine with 32 logical CPUs, so while 830ms may seem like it’s not worth worrying about, it actually represents ~25 seconds of work spread across those 31 cores (32 minus 1 for the thread that starts the jobs). That feels like it’s way too long for what this is doing, especially with the optimizations we previously made to the unwind data extraction.

We would expect most time to be taken up by the conversion process, since that does the actual work, whereas the upload should just be copying memory from user to kernelspace, and the insert into the outer map should be very fast. But looking at the timeline for the various JobScheduler threads we see surprisingly little actual work happening (i.e. green colors), some minor blips here and there, and a whole lot of waiting (i.e. red colors) instead.

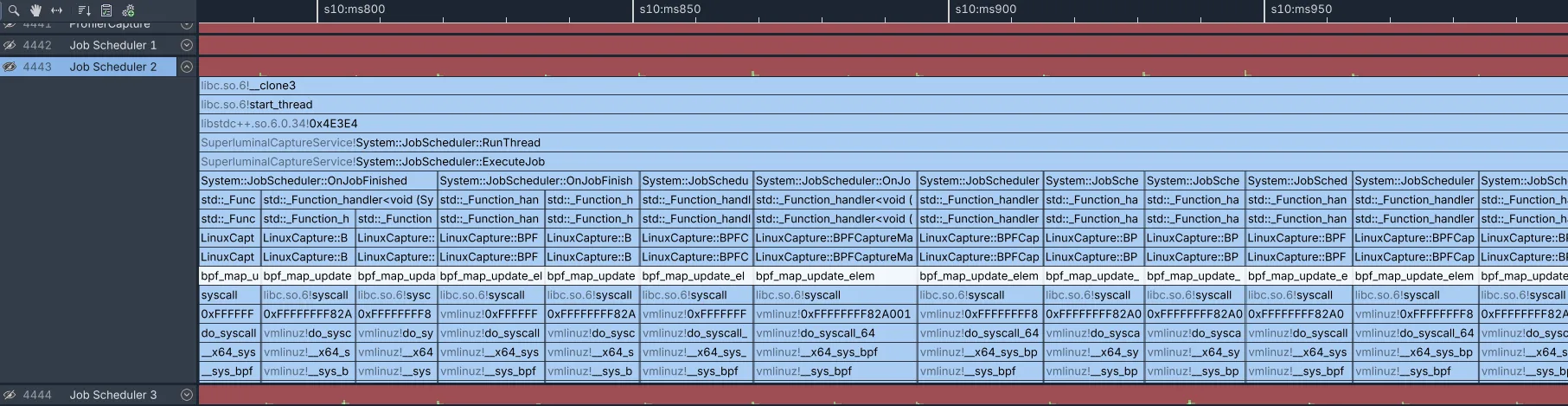

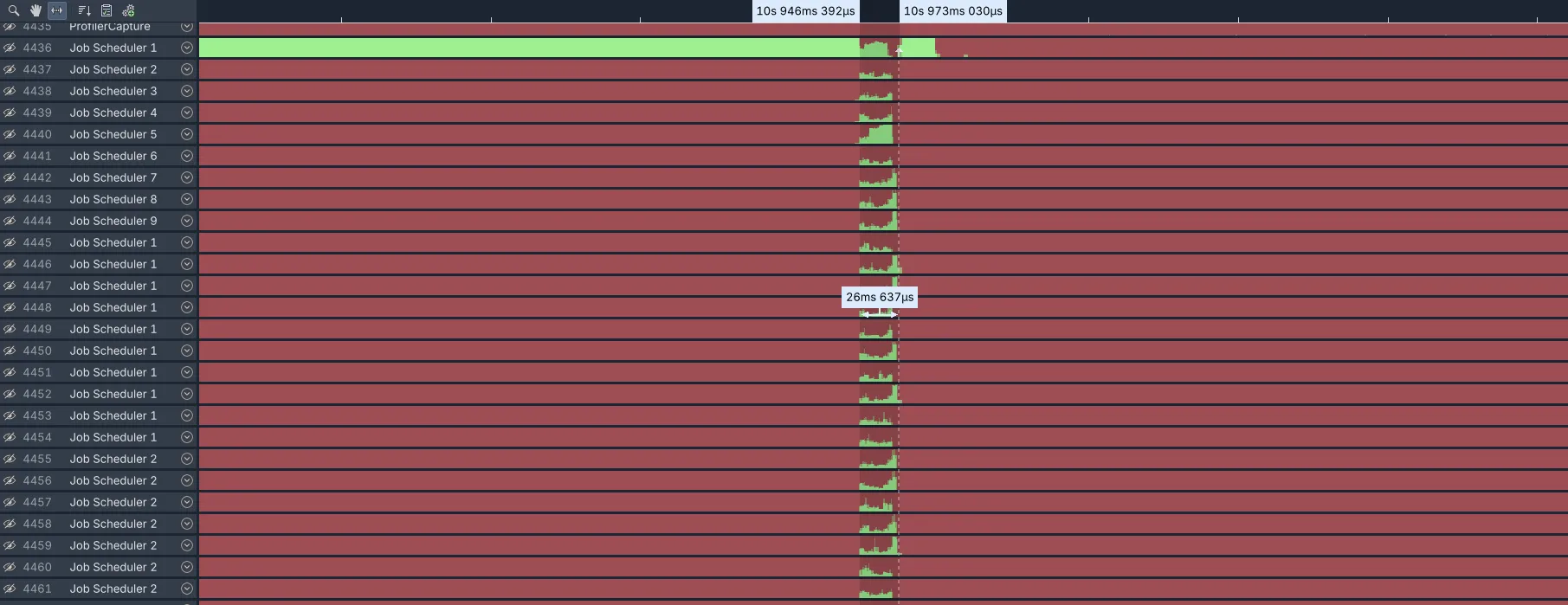

Expanding one of the threads that’s spending all its time waiting and zooming in a bit, we can see what it’s doing in detail:

This is very unexpected.

Just at a glance you can immediately see all time is being taken up by bpf_map_update_elem, highlighted in white. This function is responsible for inserting the unwind data in the outer eBPF map as described above. While there might reasonably be some overhead involved with copying data across the user/kernel boundary, this is excessive.

The function statistics show that there’s a total of 25 seconds in this function alone across all job scheduler threads, with each call taking ~18ms on average:

Function Name: bpf_map_update_elem

Number of calls: 1363

Total time: 25s 188ms 912µs

Maximum: 82ms 870µs

Top Quartile: 18ms 940µs

Average: 18ms 480µs

Median: 17ms 708µs

Bottom Quartile: 15ms 932µs

Minimum: 123µsWe can also see that when the thread is executing this function, it is in a wait state: the thread overview at the top of the thread shows the red color. This means the function is not actually doing any work: it’s waiting on something. By clicking on the corresponding wait state (i.e. one of the red areas), we can see the callstack that caused that thread to block. In this case the stack that caused the wait looks like this, with the relevant frames highlighted:

So it looks like the bpf_map_update_elem userspace function results in a map_update_elem syscall in the kernel, which calls synchronize_rcu_normal, which is what eventually causes the thread to switch out. This is where you’d normally reach the limit of what you can do with regards to optimization, since this is all happening in kernelspace.

Linux, however, is open source, which means we can dig into the kernel source to better understand what’s going on here.

Down the rabbit hole

Let’s look at map_update_elem first. This is the implementation of the syscall that bpf_map_update_elem eventually results in. Most of the function is not that interesting, just sanity checking inputs. The actual work the function is doing looks like this:

err = bpf_map_update_value(map, fd_file(f), key, value, attr->flags);

if (!err)

maybe_wait_bpf_programs(map);The bpf_map_update_value function being called here is a helper function that actually updates the value for the specified key. We can see that there is no direct call to the synchronize_rcu_normal function we’re looking for, but we do see a call to maybe_wait_bpf_programs when bpf_map_update_value succeeds.

Let’s look at the code for it:

static void maybe_wait_bpf_programs(struct bpf_map *map)

{

/* Wait for any running non-sleepable BPF programs to complete so that

* userspace, when we return to it, knows that all non-sleepable

* programs that could be running use the new map value. For sleepable

* BPF programs, synchronize_rcu_tasks_trace() should be used to wait

* for the completions of these programs, but considering the waiting

* time can be very long and userspace may think it will hang forever,

* so don't handle sleepable BPF programs now.

*/

if (map->map_type == BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH_OF_MAPS ||

map->map_type == BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY_OF_MAPS)

synchronize_rcu();

}So we found our call to synchronize_rcu. There are a few things of note here. First of all, this call only happens when the map being updated is of type BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH_OF_MAPS or BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY_OF_MAPS. These map types are also known as “map-in-map” types. And it so happens that we’re indeed updating a map of type BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY_OF_MAPS as described earlier.

It is very interesting that the call to synchronize_rcu is conditional on the type of the map being updated. If the call was unconditional, then it’s probably there for a very good reason. But the fact that it’s conditional means that there are code paths where this expensive call isn’t needed (i.e. for regular map types), and so that might be an indication we could do something about this.

There is also a comment that explains what this code aims to achieve, though it’s hard to understand the comment without more knowledge of how eBPF works, and in particular how synchronization between userspace & kernelspace works when it comes to data structures like eBPF maps.

So let’s unpack that first.

Synchronization without waiting

As we described earlier, eBPF maps are used for bi-directional data exchange between kernel & userspace. Let’s assume we have an eBPF program that looks like this (pseudocode-ish):

// Equivalent to std::vector<std::vector<UnwindRow>> as described earlier

BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY_OF_MAPS unwindData;

void ContextSwitchHandler()

{

int key = 10; // some key uniquely identifying a particular binary

// find the inner array for the key; equivalent to std::vector<UnwindRow>

void* binaryUnwindData = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&unwindData, &key);

// do something with binaryUnwindData, for example, unwind the stack

}The question is: what would you expect to happen when the value for a key in a map (in this case 10) is updated from userspace (via bpf_map_update_elem), while there are still eBPF programs running in kernelspace that are using the “previous” value for that key (in this case binaryUnwindData)?

This kind of concurrent access to a shared datastructure (in this case the eBPF map) requires some kind of synchronization between reader (the eBPF program) and the writer (the userspace program) to prevent the reader from getting its data pulled out from under it. Without synchronization, you have the problem that when the value is updated and the old value is deleted, any readers of that old value may be left with a dangling pointer.

The way the eBPF system (and indeed, the kernel in general) deals with these kinds of synchronization issues is quite elegant.

The key insight is that the synchronization problem here isn’t that the value is updated, the problem is that the old value is deleted. Taking the example of our eBPF program above, this program could continue working with binaryUnwindData just fine, even if the value for key 10 in the map is replaced with a new value, as long as it’s guaranteed that the memory containing binaryUnwindData is not freed until after the eBPF program finishes executing.

The way the kernel makes this guarantee is in essence quite simple. Instead of deleting the old value immediately after an update, the deletion of the old value is queued on a special kernel thread. This kernel thread, typically called rcu_sched or rcu_preempt, waits for the system to reach a state where it is guaranteed that no readers are still accessing any old data. This state is called the “quiescent state”, and the time it takes for the system to reach this state is called the “grace period”. Once the system reaches this state, the kernel thread deletes any queued old values via their associated callback.

The Linux kernel calls this system the Read-Copy-Update, or RCU, system. The reality behind this system/how it works is of course much more complicated than this (extremely) simplified description. For example, the way the kernel determines that the system has reached the quiescent state is quite complicated.

The full details on how this system works are outside the scope of this article, but if you’re curious, see the official RCU documentation or this excellent article.

An important observation about this system is that it’s non-blocking: since the deletion is deferred, the writer doesn’t have to wait for the deletion to complete. In our case, the writer is map_update_elem (via bpf_map_update_elem) and for non-map-in-map types it returns immediately after updating the value, while the kernel handles freeing the old value at some later point in time.

Single-threading with extra steps

Armed with this knowledge we can attempt to understand the comment in maybe_wait_bpf_programs again. The relevant part of the comment is this, stripped of the parts that aren’t relevant to understanding this issue:

Wait for any running BPF programs to complete so that userspace, when we return to it, knows that all programs that could be running use the new map value

So what this code is trying to achieve is in some ways the opposite of what bpf_map_update_elem does for non-map-in-map types.

As we just saw, for the regular case, any eBPF programs that are running concurrently with bpf_map_update_elem will continue running with whatever value they retrieved from the map, while bpf_map_update_elem immediately returns to the caller after updating the map. There is therefore no guarantee which “version” of the value for the updated key is in use at any given point in time: it could be the old value, the new value, or a mix of the two.

However, per the comment, for map-in-map types it is apparently important to guarantee that after bpf_map_update_elem returns, the old value is no longer in use: any running eBPF programs should be using the new value. But, since it is not possible to “update” (i.e. patch) already-running eBPF programs to use the new value, there is only one way for bpf_map_update_elem to achieve that guarantee, and that is by waiting for the system to reach the quiescent state we described in the previous section.

That’s exactly what synchronize_rcu does: it blocks until the system reaches that state, turning the normally asynchronous bpf_map_update_elem into a blocking operation. It is essentially a global synchronization point.

That also explains the performance issue we’re seeing. The blocking wait for the system to reach the quiescent state can take an indeterminate amount of time, and is dependent on the state of the system. This can potentially take many milliseconds (we’ve measured 8-20ms across different systems), and we’re calling it across 31 threads.

What’s happening is that we read and convert the unwind data across our job scheduler threads. This runs in parallel and takes very little time, due to previously made optimizations. All jobs then attempt to upload the unwind data they just converted at approximately the same time, and they all hit this blocking wait in bpf_map_update_elem simultaneously. The blocking waits via synchronize_rcu then finish in sequence, which serializes the upload, making the upload step effectively single threaded. After that’s done, the process repeats.

But why

So that’s the what of the performance issue we’re seeing: we’re hitting an expensive synchronization point on every update. But to determine what (if anything) we can do about this, we also need to understand the why:

- Why is this guarantee about the new value of the map important?

- Why is it apparently only important for these two types of maps, and not the many other map types?

To answer these questions, let’s look at the commit that introduced this code:

The map-in-map frequently serves as a mechanism for atomic snapshotting of state that a BPF program might record. The current implementation is dangerous to use in this way, however, since userspace has no way of knowing when all programs that might have retrieved the “old” value of the map may have completed.

This change ensures that map update operations on map-in-map map types always wait for all references to the old map to drop before returning to userspace.

…that didn’t really help. Fortunately, development on the Linux kernel happens mostly in the open, and each patch has a corresponding mailing list discussion associated with it. In this case, that discussion can be found here. You can read it if you’re interested, but the summary is that this code was added to support the following scenario.

Let’s say you have an eBPF program that looks something like this (pseudocode):

// The statistics we're interested in tracking

enum EStatistics

{

EStatistics_Duration,

// ...

}

// Record various EStatistics for context switches. Equivalent to std::unordered_map<EStatistics, std::vector<uint64>>

BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH_OF_MAPS recordedCSwitchStatistics;

void ContextSwitchHandler()

{

__u64 start = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

// ... perform potentially expensive work here ...

__u64 duration = bpf_ktime_get_ns() - start;

// find the inner array for the key; equivalent to std::vector<uint64>

int key = EStatistics_Duration;

void* durationStatistics = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&recordedCSwitchStatistics, &key);

// add the duration of this event to the array; equivalent to timestampStatistics.push_back(duration)

bpf_map_update_elem(durationStatistics, nextIndex++, duration);

}So this is an eBPF program that runs on every context switch. It does some work to handle the context switch, and it wants to report how long it took back to userspace. To do so, there is a BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH_OF_MAPS containing statistics. In this case there’s just EStatistics_Duration, but there could be others.

On every run of this program, it records the start & end timestamps of the work it’s doing to calculate the duration. Then it adds that duration to the statistics map. The inner map in this case is a list of all individual durations.

Now, the goal here is for the userspace controlling program to periodically read out the statistics that have been logged so far. Again in pseudocode, this could look like this:

void readStatisticsFromEBPF()

{

// get the current inner array with the statistics

int key = EStatistics_Duration;

void* currentDurationStatistics = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&recordedCSwitchStatistics, &key);

// do something with the statistics

}The problem is that there’s now unsynchronized concurrent access to currentDurationStatistics: while userspace is reading the values from the map, the eBPF program can still be writing statistics to it. For this inner map type (BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY), concurrent reads and writes aren’t automatically synchronized: it’s essentially shared memory without built-in locking. This is a race because userspace could read a partially updated array or read while eBPF is writing to it, leading to inconsistent data.

We can attempt to solve this by having two arrays: one that userspace is reading from, and one that eBPF is writing to, essentially double buffering:

void readStatisticsFromEBPF()

{

// get the current inner array with the statistics

int key = EStatistics_Duration;

void* oldDurationStatistics = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&recordedCSwitchStatistics, &key);

// replace (swap) the array in the map with a new one so that eBPF starts writing to that one

void* newDurationStatistics = create_array(1024);

bpf_map_update_elem(&recordedCSwitchStatistics, &key, newDurationStatistics);

// do something with the statistics

}This almost works, but the problem is that bpf_map_update_elem is not atomic: as we saw before, it updates the value for the key (in this case EStatistics_Duration) and then returns before all readers have finished. This means that after it returns, there may still be eBPF programs running that are making use of oldDurationStatistics.

So this is still a race, and it is this race that the commit fixes: with the added synchronize_rcu call, bpf_map_update_elem is atomic for map-in-map types. After it returns, it is guaranteed that the old value of the key (in this case oldDurationStatistics) is no longer in use by any eBPF programs and is thus safe to do with whatever you want.

Reading the discussion, before ending up at the final commit, the patch went through several iterations.

It started out as a new BPF_SYNCHRONIZE_MAP_TO_MAP_REFERENCES command (syscall) in eBPF that could be issued from userspace as an explicit synchronization point where needed. The maintainers felt that this was exposing too many eBPF implementation details to userspace, and that it would be hard for users to understand exactly what the new command does and when it should be used.

Instead, they suggested just always doing this sync in bpf_map_update_elem for map-in-map types:

I believe the only issue being discussed is user space doesn’t know when it’s ok to start draining the inner map when it was replaced by bpf_map_update syscall command with another map, right? If we agree on that, should bpf_map_update handle it then? Wouldn’t it be much easier to understand and use from user pov?

The original submitter responded that it didn’t seem right to force this synchronization on all users, given the relatively niche usecase:

Maybe with a new BPF_SYNCHRONIZE flag for BPF_MAP_UPDATE_ELEM and BPF_MAP_DELETE_ELEM. Otherwise, it seems wrong to make every user of these commands pay for synchronization that only a few will need.

The maintainers still felt that it would be good idea, as the cost of this was anticipated to be small:

I don’t think extra flag is needed. Extra sync_rcu() for map-in-map is useful for all users. I would consider it a bugfix, since users that examine deleted map have this race today and removing the race is always a good thing especially since the cost is small.

As we’ve seen, however, the cost of this is far from small, but that’s hindsight for you.

Optimizing it

Now that we thoroughly understand the code and problem, we can start thinking about ways to resolve it. Let’s consider our options, starting from the most direct approach.

The most obvious fix would be to remove this sync point from bpf_map_update_elem for map-in-map types and to change it to be an optional sync via an opt-in flag instead, as originally suggested on the mailing list. Unfortunately, this behavior has been in the kernel since 2018. That makes it impossible to change, since any modifications might break existing programs that (perhaps unknowingly) depend on this behavior1, and as we all know “WE DO NOT BREAK USERSPACE”2. So that’s not a real option.

The next most obvious fix would be to make use of batched eBPF map updates. Right now, the problem is that we’re uploading the unwind data for each binary individually using separate bpf_map_update_elem calls, which means we’re hitting this sync point for each upload. The eBPF API also has a function bpf_map_update_batch since kernel 5.6, which can update multiple elements. Using this function would mean this sync point is hit only once per batch.

For the precache step this would be a perfect fit. We know up front how many binaries we need to upload, so we can relatively simply divide them in batches, which are then all uploaded at the same time. This might still hit the sync point across multiple threads as before, but due to the batching, the number of sync points is much lower. For example, if we choose a batch size of 100, you would only hit the sync point 14 times instead of once per job. That would be a massive improvement.

That being said, the precache step is not the only time where we upload unwind data to eBPF. When a program is running, it might load in (many) additional shared libraries. For example, some applications we’ve tested against dynamically load hundreds of shared libraries at startup. When a shared library is loaded, we also need to upload the corresponding unwind data.

In that case we don’t want to batch uploads, because that increases the latency between the time a library is loaded and the time the unwind data is made available for unwinding to eBPF. This means that when the rate of shared library loading is high, you would still run into this perf issue. We needed a more general solution, so let’s see what other options there are.

Opting out

As we saw, in the original discussion on the mailing list, it was suggested that this explicit sync point should be a flag instead of the default behavior. The patch went the other way, but now that it’s the default, we can also consider adding an opt-out flag to the eBPF API to disable this behavior for cases (like ours) where you know that this is not the behavior you want.

Adding such an opt-out flag is exactly what we suggested on the eBPF kernel mailing list. The discussion around this was productive, initially leaning towards acceptance. But then somebody asked whether modifying the kernel to use synchronize_rcu_expedited instead of synchronize_rcu in this case made any difference to performance.

We weren’t aware of that function beforehand, but reading up on it, synchronize_rcu_expedited is a version of synchronize_rcu that’s supposed to reach the quiescent state of the system much faster. It was a good suggestion to at least try out, since it would be a less invasive change than adding an entirely new userspace flag would be. If this suggestion worked, it would mean the performance of bpf_map_update_elem would just transparently improve for all users, without needing to be aware of a new flag.

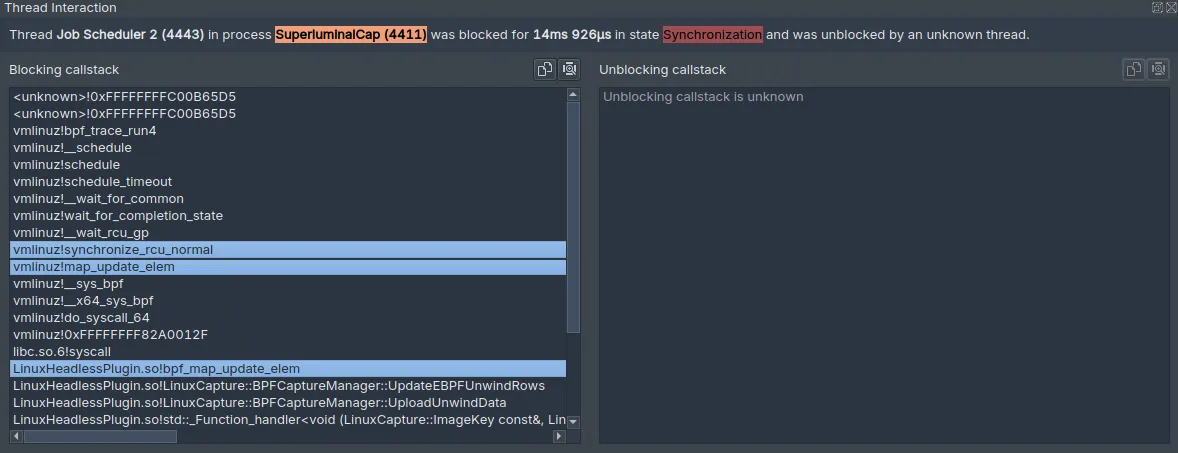

This required compiling our own kernel, which took some doing, but we were able to test this change when we got that running. Did it make a difference? See for yourself, and note that this screenshot is taken at the same zoom level as the original:

It makes a huge difference. The total time for the precache step now takes a total of ~26ms instead of the ~830ms it previously did, or 31x faster. Looking at the functions statistics for bpf_map_update_elem shows that the average time in this function is now 59 microseconds instead of the 18ms it was before, or 305x faster, for a total time of 80ms across the same 31 threads. That is much more reasonable compared to where we started.

While adding an opt-out flag would get this down even further, at this point we felt it was not worth adding that flag anymore, given the other concerns around exposing a new userspace flag.

Why wasn’t this found before

It’s interesting to think about why this bottleneck wasn’t found before, given that this code was introduced in 2018.

When you read articles about profiling on Linux, you’ll often encounter the terms “on-cpu” vs “off-cpu” profiling. On-cpu analysis involves figuring out what code that’s actually running is doing and is typically what a sampling profiler does. Off-cpu analysis in contrast is about figuring out what threads that aren’t currently running are doing, i.e. to investigate what they’re waiting on (a lock, network, etc).

These two kinds of analyses are often described as things you look at separately, with “on cpu” being seen as the thing you look at primarily, and “off cpu” as something you look at occasionally when you need to. This is reflected in the defaults of tools such as perf: when you record using a default commandline such as perf record -o ./perf.data --call-graph dwarf --all-cpus only sampling data (i.e. “on cpu”) will be recorded. It is possible to perform off-cpu analysis with perf, but it requires being aware of the difference, and the specific commandline arguments that are needed to enable it.

In contrast, in Superluminal we take the view that the distinction between the two is irrelevant: when profiling you’re always interested in where your time is going. It doesn’t matter whether your program is spending its time actively executing code (on-cpu) or whether it’s waiting for something (off-cpu). Both things contribute to the total time taken by your program and in today’s multi-core world, off-cpu analysis is as important as on-cpu analysis to understand the performance of software. We therefore always collect both on-cpu and off-cpu data by default to give you the complete picture.

This article hopefully demonstrates why: the bottleneck we found went undetected for 8 years because most performance analysis on Linux is done using purely sampling profilers. In a sampling profiler this bottleneck is invisible, because the root problem is that the bpf_map_update_elem enters a wait state via synchronize_rcu and it’s not executing any code. As a test, now that we know what the issue is, we tried using perf in sampling-only mode to find the same bottleneck, and as expected, perf reported bpf_map_update_elem as taking almost no time at all.

An instrumenting profiler would have done slightly better: even if you’d thought to mark up bpf_map_update_elem, which you most likely wouldn’t have, with instrumentation you’d at least be able to see that the function had high wall-clock time. But it wouldn’t be able to give you any information about why the function takes a long time, since you can only instrument your own code, and not the kernel itself.

Because Superluminal shows both sampling and wait information on a wall-clock timeline with full kernel visibility, however, the problem was immediately obvious and allowed us to find & fix the problem.

Wrapping up

What started out as a regular profiling session of our own code ended up with a trip down the kernel rabbithole, where we discovered and fixed an 8-year-old bottleneck affecting all eBPF map-in-map users. bpf_map_update_elem is now much faster for these map types, resulting in a 31x speedup of capture startup time on our end.

We submitted a patch with this change, which was accepted and will be shipped in the Linux 6.19 kernel update. If you’re using BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY_OF_MAPS or BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH_OF_MAPS in eBPF, your program will transparently get much faster from 6.19.

So! I guess we’re kernel contributors now.

Footnotes

-

Hyrum’s law: with a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody. ↩

-

This is from the kernel’s point of view. On Linux, the job of breaking userspace is left to

glibcinstead, which is more than happy to do so. But that’s another story. ↩